In our newsletter last month, we talked about getting organized and ready for foaling out your mare (click here for this news article). Being prepared for the foaling process is of paramount importance, in order to have an enjoyable and successful outcome for the mare, foal, breeders, owners, and attendants. As you are preparing your barn for the foaling, don’t forget that the mare has a chorus of events taking place internally to prepare her body for parturition, transition to lactation, and uterine involution. Whether these events are noticeable or not, they are a necessity for the proper progression of labor and delivery. In our blog article this month Dr. Scofield reviews the stages of parturition and summarizes the hormonal events that are occurring with your mare during this incredible physiological process.

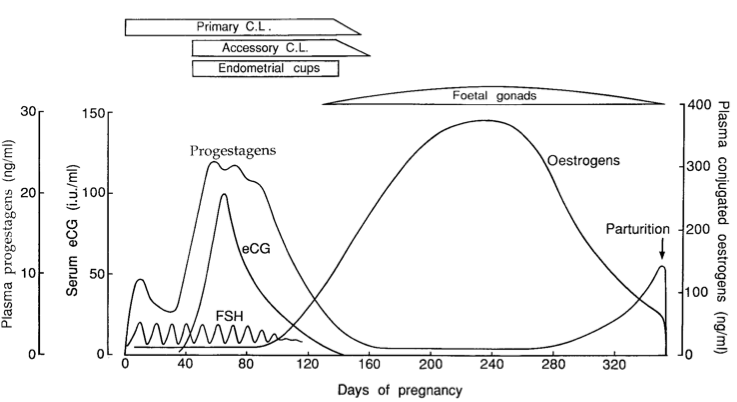

The late term mare is experiencing rapid growth of the fetus in size and weight, preparing for lactation, and preparing for delivery. There are six main hormones at play to prepare the fetus and mare for the foaling process.

- Total Estrogen levels are falling as a mare approaches term. Estrogens, produced by the fetal gonads, peak by 8 months and decrease in the last trimester. Estradiol-17β (E2) however, has an appreciable rise that has local effects to up-regulate myometrial oxtocin receptors and may facilitate prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) synthesis. High levels of estrogens near term help the mare respond to higher magnitude pulses of oxytocin and to have stronger myometrial contractions that are needed for delivery.

- Progesterone is a hormone most commonly associated with pregnancy. It is however, only produced by the corpus luteum. By mid term, progesterone is replaced by a myriad of progestagens, termed 5α-pregnanes, produced from the feto-placental unit. As parturition approaches, these progestagens are declining and reach baseline after foaling. Their specific effects are unknown, but most likely help keep a mare’s uterus quiescent and can help regulate oxytocin and progesterone receptor up-regulation.

- Relaxin levels are increasing in the second half of pregnancy and actually spike during stage II of labor when oxytocin pulses are highest. Relaxin is partially responsible for the noticeable changes to your mare’s perineum, tail head, and vulva late term.

- Levels of prostaglandin E2 rise toward term and during stage I of labor, it works in concert with Relaxin to soften a mare’s cervix and increase the endometrial sensitivity to high levels of other prostaglandins that occur in stage II.

- Oxytocin, released by the posterior pituitary, remains at a very low level until stage II of labor. During stage II, as discussed later in this blog, the fetus’ presence in the birth canal connects a positive neuroendocrine feedback loop (the Ferguson Reflex) and causes marked endometrial contractions. Exogenously administered oxytocin is used to induce parturition in late term mares, but that is a topic for another discussion.

- Cortisol may be one of the more important hormones involved in this process. A rise in fetal cortisol production occurs 24-48 hours prior to delivery. This rise is due to maturation of the fetal adrenal glands and their ability to respond to signals to make cortisol. The ability of the fetus to respond to ACTH and release adrenal cortisol shows a readiness to survive in an ex utero environment. Rising cortisol levels alter the steroidogenic pathways in the placenta and shifts production towards estrogens instead of progestagens. Furthermore, cortisol is responsible for the final maturation and production of pulmonary surfactant, as well as gastrointestinal and hepatic enzyme systems.

With all these hormonal changes occurring in the mare and fetus, it is hard to overlook how this manifests in the mare. Parturition is divided into three stages based upon what is occurring both internally and externally in the mare.

Stage I

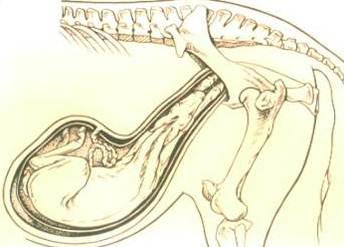

Stage I of labor begins with small uterine contractions. Small oxytocin pulses from the posterior pituitary and increasing prostaglandins (PG) begin uterine contractions that position the fetus in the correct position for delivery. The fetus at this stage is effectively lying down with his back on the belly of the mare and feet towards the spine of the dam. In this position, the head and legs are flexed. For a normal parturition, the fetus must first rotate and extend the front limbs and head. Once this is accomplished, the fetus usually has its front limbs engaged at the internal os of the mare’s cervix and is positioned in the classic, cranial longitudinal presentation, dorsal sacral position, with head and front legs extended. Small rises in PG will cause the mare to sweat and coupled with oxytocin, cause uterine contractions that can cause the mare to act mildly colicky. She may be restless, show patchy sweat patterns, paw at the ground, and leak milk. Something to keep in mind, since oxytocin controls both milk letdown (which is very different than inducing lactation) and uterine contractility, usually uterine contractility and milk letdown are coupled clinically.

Stage I of labor begins with small uterine contractions. Small oxytocin pulses from the posterior pituitary and increasing prostaglandins (PG) begin uterine contractions that position the fetus in the correct position for delivery. The fetus at this stage is effectively lying down with his back on the belly of the mare and feet towards the spine of the dam. In this position, the head and legs are flexed. For a normal parturition, the fetus must first rotate and extend the front limbs and head. Once this is accomplished, the fetus usually has its front limbs engaged at the internal os of the mare’s cervix and is positioned in the classic, cranial longitudinal presentation, dorsal sacral position, with head and front legs extended. Small rises in PG will cause the mare to sweat and coupled with oxytocin, cause uterine contractions that can cause the mare to act mildly colicky. She may be restless, show patchy sweat patterns, paw at the ground, and leak milk. Something to keep in mind, since oxytocin controls both milk letdown (which is very different than inducing lactation) and uterine contractility, usually uterine contractility and milk letdown are coupled clinically.

Stage I lasts for 1-4 hour hours, but the mare can delay the progression slightly so that she foals at a time when she feels comfortable. Stage I is shorter in multiparous mares and ends abruptly when the mare ruptures her chorioallantoic membrane or “breaks her water.”

Stage II

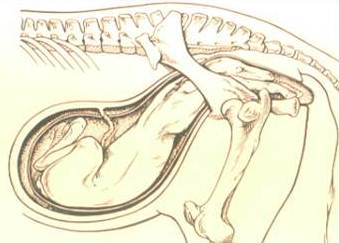

Stage II is what most people consider the foaling proper. In mares, which differ from other species, stage II is a very quick event. As soon as the fetal feet engage the mare’s cervix, dilation of the cervix and anterior vagina causes a large increase in oxytocin release from the posterior pituitary gland. The completion of this neuroendocrine loop is termed the Ferguson Reflex, and causes the sensitized uterine endometrium and myometrium to have strong contractions to help move the fetus along. Mares have high levels of oxytocin receptors per square centimeter of uterine myometrium, allowing for such a strong response to oxytocin from the posterior pituitary. During this stage, a strong abdominal component also helps propel the fetus through the birth canal. A grayish translucent membrane, the amnion, will be the first tissue to pass the mare’s vulva, followed by two staggered front limbs, nose, and finally shoulders. In the horse, the foal’s shoulders are usually the most difficult part of the foal to pass the pelvic canal. By staggering the front limbs, it narrows the foal’s shoulders and helps them to pass the pelvic inlet of mare. As the fetus passes the vulva, stage II ends and stage III begins. In the event that the mare lays and rests while the foal’s feet remain in the vaginal vault or vestibule, I still consider stage II to have passed.

Stage II is what most people consider the foaling proper. In mares, which differ from other species, stage II is a very quick event. As soon as the fetal feet engage the mare’s cervix, dilation of the cervix and anterior vagina causes a large increase in oxytocin release from the posterior pituitary gland. The completion of this neuroendocrine loop is termed the Ferguson Reflex, and causes the sensitized uterine endometrium and myometrium to have strong contractions to help move the fetus along. Mares have high levels of oxytocin receptors per square centimeter of uterine myometrium, allowing for such a strong response to oxytocin from the posterior pituitary. During this stage, a strong abdominal component also helps propel the fetus through the birth canal. A grayish translucent membrane, the amnion, will be the first tissue to pass the mare’s vulva, followed by two staggered front limbs, nose, and finally shoulders. In the horse, the foal’s shoulders are usually the most difficult part of the foal to pass the pelvic canal. By staggering the front limbs, it narrows the foal’s shoulders and helps them to pass the pelvic inlet of mare. As the fetus passes the vulva, stage II ends and stage III begins. In the event that the mare lays and rests while the foal’s feet remain in the vaginal vault or vestibule, I still consider stage II to have passed.

What is so impressive about the mare, in my opinion, is that stage II only lasts around10-30 minutes. It averages 15-18 minutes, and when stage II lasts longer than 30 minutes, it increases the chances of neonatal disease, neonatal death, and complications to the mare.

Every 10-minute increase in stage II (longer than 30 minutes) corresponds to a 10% increase in the risk of a stillborn foal and a 16% increase in the foal not surviving until hospital discharge.

With a foaling mare, early intervention and correction of fetal mal-positioning greatly increases the likelihood of a foal survival.

Mares that proceed longer than 20 minutes from rupture of the chorioallantois without any fetal parts appearing should be investigated for fetal malposition. Mares that fail to progress significantly over the 20-30 minute window of stage II should also be investigated for fetal malposition. Reported dystocia rates range from 5-10% of all foaling mares, so it is a real event that must be planned for appropriately.

Stage III

Stage III of parturition begins when the entirety of the foal is out of the dam and consists of the passage of the fetal membranes or placenta. This can take anywhere from 15 minutes to 3 hours. Depending on where you practice, where you were educated, the value of the horse, and the time of day, there are many different thoughts as to when a placenta is considered retained and what to do about it. Classically, fetal membranes should be passed within three hours of the birth of the foal. Similarly, membranes retained longer than three hours were considered an emergent condition and required veterinary intervention. There is some debate and conversation among veterinarians regarding this timeline and the necessity of early intervention, but timing and a treatment plan for the mare with retained fetal membranes should be discussed with your farm veterinarian.

Stage III of parturition begins when the entirety of the foal is out of the dam and consists of the passage of the fetal membranes or placenta. This can take anywhere from 15 minutes to 3 hours. Depending on where you practice, where you were educated, the value of the horse, and the time of day, there are many different thoughts as to when a placenta is considered retained and what to do about it. Classically, fetal membranes should be passed within three hours of the birth of the foal. Similarly, membranes retained longer than three hours were considered an emergent condition and required veterinary intervention. There is some debate and conversation among veterinarians regarding this timeline and the necessity of early intervention, but timing and a treatment plan for the mare with retained fetal membranes should be discussed with your farm veterinarian.

Stage III averages 1.5 hours, but commonly the membranes may fall from mare when she stands or when the foal begins to nurse or suckle near a mare’s udder. Remember, that oxytocin release in response to the foal causes milk letdown and uterine contractility to help expel the membranes. Uterine involution begins immediately as the chorionic villi detach from the membrane. Uterine size, weight, appearance, and fluid content will repair very quickly on a gross level. Every placenta should be examined thoroughly regarding gross appearance, abnormal chorionic findings, presence of both horn tips, and weight.

All aspects of uterine involution are crucial for the mare. Mares can, in certain instances, be bred and have normal pregnancies on her foal heat in just a few short days. Many aspects of foal heat breeding, uterine involution, ovarian activity, and neonatal care are beyond the scope of this month’s blog, but stay tuned and I will touch on some of them in the coming months. Best of luck applying this information to your foaling mares, and have a great foaling season!