“I just purchased one very expensive dose of frozen semen from this incredible stallion. Is it OK to split the dose and breed two mares to try and get two foals?” or “The stallion owner only provides one dose per heat cycle and my vet would like to use a timed insemination protocol. Is it OK to split the dose and inseminate twice on the heat cycle?” At SBS we have heard these questions or some variation of them many times over the years. The answers are not simple ones. This blog article will follow up on two previous blogs that are also important in understanding the issue. See the recent blogs What Exactly is a Dose of Frozen Semen? and What is Progressive Motility?

First of all, if the reason for splitting the dose is an attempt to obtain multiple pregnancies then you must make sure that the frozen semen sales contract or breeding contract with the stallion owner allows for the breeding of multiple mares and registration of resulting foals. For the purpose of this discussion we will assume that you have the right to breed as many mares as you like with the dose of semen.

A number of variables can influence the pregnancy rates obtained when inseminating mares with frozen semen. First and perhaps most importantly is the inherent fertility of both the mare and stallion involved. This is true for inseminations with frozen, cooled or fresh semen as well as natural service. As the degree of semen processing increases from natural service to cooling and freezing, other variables also come into play. The quality of the collected ejaculate, semen handling technique, extenders used, preservation techniques used and the inherent ability of sperm from individual stallions to withstand the stresses associated with cooling and or freezing and thawing all influence the fertility of the semen sample.

The generally accepted recommendation for commercial frozen semen is that a “dose” should contain a minimum of 200 million progressively motile sperm and possess >30% progressive motility upon thawing. Commercial doses of frozen semen supplied by reputable freezing labs “should” upon thawing contain sufficient numbers of functionally competent sperm to achieve acceptable pregnancy rates following properly timed insemination into reproductively healthy mares. This recommendation is based on extrapolation from fresh semen trials, a few controlled studies with frozen semen and accumulated fertility data from large commercial breeding programs. The problem with this type of general recommendation is that in the horse, unlike with cattle, the variability of fertility between individual stallions is very large and may not be highly correlated with the motility of the sperm in the ejaculate. Some stallions can achieve high fertility with much fewer motile sperm per insemination than the recommended dose while others may require much higher than the recommended dose. For a more detailed discussion of this point please refer to our blog It Only Takes One….Right? and the FAQ Why does SBS recommend selling frozen semen as part of a contract rather than by the dose?

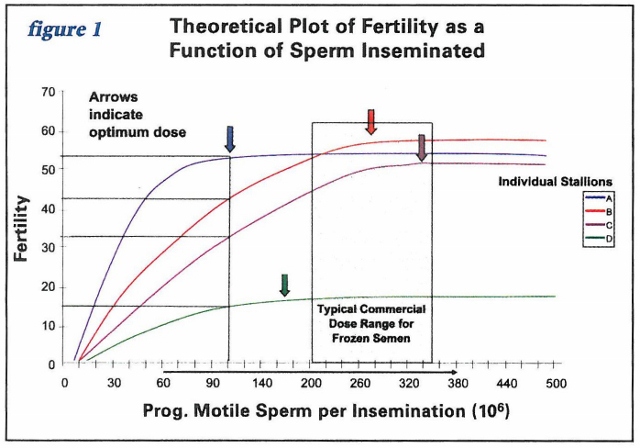

For every stallion there is a minimum threshold in the number of sperm inseminated on the dose response curve (see figure 1) where fertility will drop significantly. If fewer than that number of functionally competent sperm are inseminated then pregnancy rates will suffer. Splitting a dose in an attempt to get two foals often leads to no foals and so this must be done very carefully. First, you must know how many sperm are in the dose that you have and also know what the quality is after thawing. At SBS we send a transaction report with all frozen semen distributed which provides detailed information on the number of sperm per dose and the expected post-thaw progressive motility for that batch of semen. If you do not have this information then you have no way of knowing how many sperm you are inseminating when you split the dose.

In figure 1, stallion A achieves maximum fertility with much fewer sperm per insemination than the other 3 stallions. Insemination of more sperm for this stallion does not further increase fertility. The appropriate dose for this stallion would be 100 million progressively motile sperm. Stallion B has a higher maximum level of fertility but it is only achieved following insemination of far more sperm. When inseminating 100 million sperm for all 4 stallions in our example, a wide range of fertility is obtained (53% for A, 42% for B, 32% for C and 15% for D). Increasing the number of sperm inseminated to 250 million for stallion A does not change fertility while increasing to 250 million sperm for stallions B and C results in a significant increase in fertility. Stallion C is capable of achieving similar fertility as stallions A and B however reaching this level of fertility requires the insemination of far more sperm. Stallion D has a low level of maximum fertility that cannot be overcome by insemination of far greater numbers of sperm. This is due to the fact that some defects of sperm are compensable and others are non-compensable.

There are numerous reports in the scientific literature of acceptable fertility achieved with low numbers of frozen-thawed spermatozoa. For highly fertile stallions and mares this can sometimes be achieved with standard insemination techniques. However, if fertility is unknown or based on results from only a small number of inseminations then it is advisable to use a deep uterine horn insemination technique. With this technique, a low dose of sperm in a small volume is deposited at the tip of the uterine horn on the side of the ovulating follicle which presumably results in more sperm entering the oviduct on the side of ovulation as compared to uterine body insemination. A veterinary specialist trained in equine reproduction who has experience and a good track record with this technique should be used in this case. Acceptable pregnancy rates in normal fertile mares have been reported clinically and in the scientific literature when 1/2, 1/4 or even 1/8th of standard doses have been inseminated from fertile stallions using this technique.

Another reason for splitting a dose is to allow the veterinarian to inseminate twice on a heat cycle using a timed insemination protocol when only one dose is available or in an attempt to inseminate both before and after ovulation. We have published data on thousands of inseminations from hundreds of stallions with frozen semen that demonstrates equal fertility in mares that are inseminated once after ovulation versus twice using a timed insemination protocol when full doses are used. We and others have also demonstrated that fertility following a single insemination of 800 million total sperm (normal SBS dose of frozen semen) within 6 hours after ovulation is the same as two inseminations of ½ doses (400 million total sperm) 12-16 hours apart timed to bracket ovulation. For a discussion on this topic see our blog The Pros and Cons of 1 or 2 Dose Insemination Protocols.

Keep in mind that some mares are susceptible to post-breeding endometritis and persistent fluid accumulation and should probably only be inseminated once on a cycle and therefore a 2 dose protocol may not be appropriate.

SBS recommends that stallion owners sell frozen semen as part of a guaranteed breeding contract and provide two full doses per cycle to minimize veterinary costs to mare owners for intensive single dose protocol management. In these cases there is likely no advantage to using a deep uterine horn insemination technique. However, if only a single dose is available or if you are purchasing valuable semen by the dose and intend to only inseminate once on the cycle with a partial dose then we caution breeders about splitting doses for the reasons discussed above. Our recommendation is to never split a dose of frozen semen if:

- your mares are not young proven fertile mares

- the number of sperm per dose or the post-thaw quality of the semen is unknown

- the fertility of frozen semen from this stallion is unknown, undocumented or based on limited data

Remember, it is better to breed one mare and get one foal than to breed 2 mares and get no foals.

If you like this article you may be interested in: